|

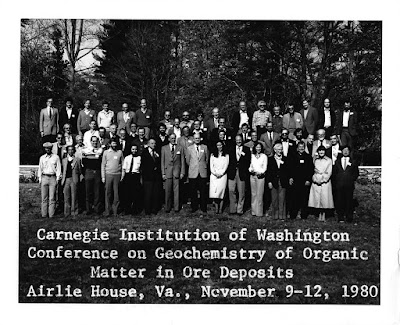

| 5 Women out of 51 attendees: Marilyn is center front row |

In the early days of my career, I

was typically one of about 5-8 women out of the 100-200 people who attended the

smaller conferences in my discipline. At larger meetings like the Geological

Society of America (GSA), there were ususally about 10 women for every 100

men. It should come as no surprise that we women were often targeted for

unwanted sexual attention, bordering on sexual harassment.

In 1983, at the International

Meeting of Organic Geochemists (IMOG) that took place in The Hague,

Netherlands, I was subjected to a particularly embarrassing situation. At all

IMOG meetings, on the next to the last day of the conference, a banquet is

held. These are no “rubber chicken” banquets—they serve shots and glasses of

local whiskies, wines, and beers. Typically, the alcoholic beverages are served

for an hour or two before the food arrives. Several times at IMOG, the food was

secondary to the liquor.

|

| 11 Women with 152 attendees. Marilyn is in 3rd row, 2nd from left. |

There is also always dancing at

these meetings. Imagine 150 men hanging around 10 or so women in 1983. My

“dance card” was always filled so to speak. Later in the evening, one of the

senior organic geochemists, Wolfgang Seifert of Chevron Oil, had had more than

enough to drink. When the next song started, he literally grabbed me and

started madly dancing. Geochemists parted and formed a circle around

us--cheering, hooting, and clapping—the kind of attention that a young

professional female scientist, 31 years old, does not need. I was powerless to

free myself. With one arm around my waist and the other holding my hand, he

lifted me off the floor, feet in the air, and swung me around and around. The

geochemists whooped even louder and laughed hysterically. I was mortified.

The end of the evening was capped

off by another encounter with a drunken organic geochemist, who blubbered his

admiration and sloppily propositioned me. Scenes like this often took place. My more sober male colleagues knew who the

serious alcoholics were and shook their heads. Often, they offered to get rid of the pesky idiot for me. In

today’s world, offensive behavior like this is no longer tolerated at

conferences or scientific meetings. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, some people thought

that women got their scientific ideas from the men they slept with. Today, this

is an absolutely ridiculous notion!

As the only senior woman scientist at

the Geophysical Lab for 30 years, I was usually the person that all of the

other women went to when they had a problem. One afternoon circa 1998, while I

was working on some data late in the day, a student knocked timidly on my door

and stuck her head in.

“Can I come in for a minute?” Sure,

I answered. She looked uncomfortable, so I asked if she wanted me to close the

office doors. She nodded and looked relieved. A visitor to her lab had followed

her into the Ladies Room, cornered her in the laboratory, and put his hands on

her where they should never have been. The student was not the type you’d think

might attract a creep like this. She kept to herself, worked odd hours, and wasn’t

the sort to wear anything close to “suggestive” clothing. I had incorrectly

assumed that a person like this would be an unusual target. On hindsight, she

was just the type of person—shy, introverted, quiet—that is picked on by

predatory men. I reported the incident to Director Charlie Prewitt, who I

describe as the “Jimmy Carter” of Geophysical Lab directors. He was pained to

hear this and acted promptly by revoking the visitor’s invitation to work at

the Lab. Within a week, the Pernicious Creep was gone.

Sexual harassment and discrimination

is usually not that easy to deal with. Often the line is “fuzzy”—did someone do

this intentionally? Was it harassment or discrimination? My next big challenge

came in the form of a lab fire, of all things. I was the Geophysical Lab’s

Safety Officer, in charge of chemicals, hazards, and compressed gases. I had

just finished cooking a lunch club meal, talking with former Postdoc Carmen

Aguilar, when the fire alarm went off in the building. Another postdoc rushed

in and shouted, “Do you know if lithium is toxic?” I thought for minute, as I was

preparing to vacate the building, then answered, “Well, they give it to people

with bipolar disorder. Can’t be too toxic. Wonder what this fire alarm is

about?”

Turns out, this postdoc had dropped

lithium metal that had been soaking in water onto the floor of the Science

Building. The linoleum floor caught fire, as the metal reacted violently with

the water, melted the glass beaker holding it, and dripped onto the floor.

Within minutes, four large fire engines came to the campus and extinguished the

fire. As Safety Officer, I needed to direct the fire fighters into the lab,

advise them on hazards, and tell them what started the fire. When the Captain

heard the word “chemical fire”, many large 6 foot 4 inch tall fire chiefs

surrounded me and demanded to know about lithium and its toxicity. The campus

was evacuated, and everyone except for a few of us was sent home. The

laboratory was cleaned up and repaired. The poor postdoc with the reactive

lithium was apologetic.

Three weeks later, four women

postdocs from our sister lab, DTM, knocked on my door. This was unusual, so

without asking we shut the outer doors and I waited. Slowly the story spilled

out. The lithium fire started in their office, by the postdoc who was showing

off by pouring bottled water directly on the lithium. The women were offended

that he wasn’t reprimanded. It didn’t seem fair to them that he had gotten away

with something this serious. It felt like special treatment, discrimination in

a sense that a man could do this, but god forbid a woman would do something so

stupid and dangerous. I went immediately to inform the current Lab Director,

who was furious with the new version of the story. How the postdoc who started

the fire was subsequently disciplined, was a mystery. We heard he was fired,

then learned he was reinstated. To me, it was symptomatic about the way in

which men seemed more entitled than the women scientists working at the lab.

A few years later, I received a

complaint from one of the Hispanic maintenance men, an unlikely person to

report sexual harassment. Carnegie hired contractors to clean our campus

buildings. I suspect some of the women cleaners might have been undocumented

workers, who were afraid to report that they were being harassed. Apparently,

at least three of the women were followed around, cornered as they worked,

asked out on “dates” by one of our maintenance supervisors. If they rebuffed

his advances, they were fired. I shared this with my senior female colleagues,

now that I was no longer the only senior woman on campus. We took the problem

to our Directors. They prevaricated, made excuses, and refused to consider

discussing the matter with the employee without further “proof”. We were angry,

disappointed, and held a meeting for all of the women on the Carnegie campus.

Eventually, years later, with a complete change in leadership, this problem was

dealt with and the harassment stopped. But it took years for this to happen.

Why should that be?

How often do we hear of Universities

like Berkeley and UC Irvine, failing to deal with serious sexual harassment

issues? Geoff Marcy and Francis Ayalla were serial harassers, yet because they

were famous scientists and brought in copious amounts of grant money,

administrators ignored the complaints. As a UC Professor, I am now required to

report anything that possibly might violate Title IX legislation. I have seen

and known, now, of the pendulum swinging the other way. Are we being too

sensitive? How are we investigating the complaints?

As new Assistant Professors, both

the men and the women, will now need to develop a better way of dealing with

sexual harassment and discrimination that seem to be surfacing in every walk of

life. For young, vulnerable women (and men), I feel that the new era is

empowering them to recognize and stop abusive behavior. It’s an aspect of my

career that I wish I hadn’t had to deal with, but I am glad I accepted the

challenge to defend those who needed it and sought justice. Always stick up for

the “little” gal or guy. It’s the right thing to do.

No comments:

Post a Comment