|

| Marilyn and Noreen in the isotope lab, 1995 |

I have several muses for my blog—former postdoc and current Frolleague Seth Newsome, Chris my husband, student Bobby Nakamoto, former colleague Tom Hoering, and the venerable Noreen Tuross. Noreen is one of those remarkable people you run across in life. She’s direct, thought provoking, and different enough to never allow her to be pigeonholed.

Noreen is a full Professor at Harvard University. She belongs there, but even though she’s been on the faculty for more than 15 years, she hasn’t developed that Harvard drawl, where “r”s are softened or dropped and a slight English character infests the tone. In fact, however, Noreen can do a fine imitation of the drawl when she wants to.

Harvard has been a good place for her. She’s had a good lab situation with a long-time research associate Linda Reynard [Now at Boise State] and a flock of very smart anthropology students. I was recently asked to write a letter of support for Noreen. The breadth of her work showcases her curiosity and creativity. Many of her papers debunk an entrenched paradigm. She probes from the side—asking questions some want to avoid. As a long-term colleague of Noreen’s I enjoyed those hunts for scientific (and isotopic) truth.

We asked the following:

· Is there an isotope tracer built into tissues from nursing and weaning an infant?

· What happens to the chemical and isotopic makeup of bones and teeth when an organism dies?

· Can we trace starvation with isotope tracers?

· What can isotopes tell us about the diets of omnivores—specifically humans?

· Is the hydrogen isotope signal in an animal from diet or drinking water or both?

· What’s the best method for analyzing isotopes in amino acids?

· Can we measure the fragments of real macromolecules from million year old fossils?

Below is re-hash of some of my favorite Noreen Tuross stories. She was there with a bucket of dry ice for the birth of my two children—to preserve the placentas for the future. She sang at my wedding. She roasted me at my retirement. Noreen embodies the strong female personality that is needed to get by as a senior scientist. Called the B-word many times by some grumpy, ineffectual colleagues, she sailed though these troubled waters without looking back.

Having women friends helps you get by. I first met Noreen in 1978. Although I’d upped my wardrobe at the Geophysical Laboratory from K-Mart specials to L.L. Bean clothing, I was certainly not fashionable. Noreen Tuross who had been working with my colleague Ed Hare on amino acids in ancient bones was getting her Masters degree from Bryn Mawr College, an excellent private women’s school on the Philadelphia Mainline. We met just prior to her around-the-world trip funded by a fellowship from the Watson Foundation. Watson, one of the founders of IBM, created a foundation that recognized students from smaller schools who had big ideas for changing their science discipline. Noreen was, and still is, a visionary with respect to weaving an understanding of medical science with the study of ancient humans.

Noreen, a natural platinum blonde, is as far away from a “dumb blonde” as you can get. The day we met, she wore tall leather boots, a mid-calf skirt, and a long woolen coat, probably from a swanky department store like Bloomingdales or Garfinkels. She spent the following year climbing into caves (in far more practical clothes) with her new husband, Dick Waldbauer, finding saber tooth tiger and other extinct animal bones that she brought back for analysis at the Geophysical Lab.

Story #1 Nursing Mothers and Isotopes: Noreen and I began a friendship in 1979 when we first shared a room at an amino acid conference honoring Carnegie’s President Phillip H. Abelson. In 1985 Noreen had finished up a PhD in medicine from Brown University and was moving with her family (including her precocious 5-year old, Jacob Waldbauer, now a Professor of Biogeochemistry at the University of Chicago) to begin a postdoc at the National Institutes of Health, working on the chemistry of bone formation. I invited them to stay with me in my small bungalow in Silver Spring Maryland while they bought a house. For about a month, they lived with me, then a single gal. They ended up buying a house within a few miles—a similar sized “small bungalow”. We became good friends.

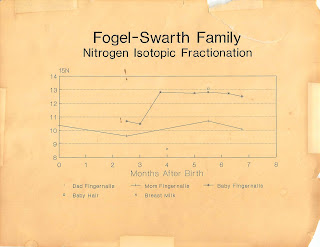

Noreen started a second postdoc at the Geophysical Lab in 1987, specializing in both modern and fossil protein studies, having training in immunology and ancient DNA methodology, as well as protein biochemistry. She wanted to investigate the nitrogen isotope fractionation between a mother and her nursing infant. This idea was important for understanding why the human population rose dramatically after the origin of agriculture. Theoretically, infants should have a nitrogen isotope composition that is slightly greater than their mothers, because “you are what you eat” plus a little bit more.

Our hypothesis was the following: prior to a secure source of food for raising children, mothers (i.e., hunter gathers) needed to nurse their children for longer periods of time. Once food could be grown and cached, mothers (e.g., agriculturalists) could wean their children earlier, get pregnant and have more children, thus leading to a rise in population. Stable isotopes from archaeological samples could tell us at what age children were weaned.

At the time of this study, I was pregnant with my daughter Dana. We eagerly anticipated her birth. I began sampling Dana’s fingernails and mine right after she was born. In addition, samples were obtained from more than a dozen other mothers and their infants who were exclusively breastfed. We found an enrichment in the heavy nitrogen isotope between mothers and infant pairs as we had hypothesized. As the babies were weaned onto solid diets comparable to what their mothers were eating, the nitrogen isotope differences between mothers and babies decreased over time (Fogel et al., 1989). After babies were fully weaned, their nitrogen isotope values were the same as their mothers’.

We then analyzed human bones from two populations: hunter-gatherers from Tennessee and corn-growing Indians from South Dakota. Contrary to our beginning hypothesis, we found that even though these two populations depended on very different sources of food, children were weaned at about the same age, roughly a year old, and their nitrogen isotope values in bones matched the adults in the population by the time they were two to three years old. The nursing effect has been measured in populations of other mammals---seals, cave bears, killer whales, as well as being a keystone work for anthropological investigations of ancient civilizations.

Story #2 Isotopes, Brachiopods and Advice: Our husbands also became friends. Serious in their own pursuits (ecology and archaeology), together they talked about baseball, played in an Old Guys Baseball League, and took watch over the kids when Noreen and I were out and about. In 1994, we all went to rural Wisconsin to dig up fossil brachiopod shells from 500 million year old rocks. Neither of us was much of a “rock person”, being more comfortable in an analytical lab or with living organisms. We bought all sorts of rock hammers, chisels, and rock bags, bringing back hundreds of kilograms of sedimentary rock full of fossils.

My favorite part of this trip was an impromptu visit to the Leinenkugel Beer Brewery. After 5 hours of rock pounding, we decided to treat our husbands and postdoc Herve Bocherens to a couple of beers. We lugged our kids along, who weren’t allowed in the bar serving the beers. Each of us adults was given two tokens to exchange for two beers. Chris watched Dana and Evan in a little playground first, while I plunked down my first token. I took my first couple of sips before he stuck his head in.

“The kids want you to come out.,” he said. “Now!” OK, I answered. “Finish my beer.”

Fifteen minutes later he came out and said, “Great beer. Your turn.” It came to little surprise to me that mid-sip, I was called out again. When he emerged again having downed my beers, he gave me one of his tokens, which I presented to the bartender.

“You’ve already had your two beers. I’ll have to ask to leave.” I was speechless.

I’d just been 86’d from a bar. I said bye to Noreen and Dick, headed out, and grumbled as Chris went in, used his token for his 3rd beer!

In 1995 we took another trip with our combined families to Hawaii to find the living like an ideal work-life trip. Noreen had rented a posh north shore Oahu mansion with a backyard pool close to the beach. While she, her son Jake, and I went Lingula hunting, the rest had fun at the beach or sightseeing. I groused at Chris when I came back to the house, tasked with work processing seawater still to be finished.

Always thinking and thoughtful, Noreen came into the garage, drinking a beer, where I was filtering liters of seawater samples on a jury-rigged setup I’d built out of bits and pieces.

“Do you want to make it to ten years?” she asked in a voice tinged with annoyance. We’d been married 9 years but I was grumbling.

“Yeah,” I said, “I’ll stop the nagging.”

Story #3 Isotopes and Molecular Biology: I was fascinated by new molecular techniques that Noreen was experimenting with at the Smithsonian Institution. When she took a leave of absence to run the Watson (founder of IBM) Foundation, I spent a sabbatical in her lab learning Western blots, protein gels, and immunology. At that time, my husband was the Director of the Jug Bay Wetlands Sanctuary on the Patuxent River in Maryland. Every year, I’d watched the rapid growth of marsh plants in spring and summer, followed by their senescence in early fall. My family spent every weekend there for almost 8 years. I decided to design a litterbag experiment. My goal was to combine molecular biology, litterbags, and stable isotopes. I learned a lot doing this!

Plants were collected from the marsh in early September. The bags were either buried in deep marsh muck or tethered to PVC pipes, where they sat on the sediment surface. Monthly, I would don hip waders and muck through the mud to pull out a couple of bags of rotting plants. The decomposed plants were gently washed free of sediment, dried, weighed, and then ground into a fine powder. I had hundreds of samples from this experiment. I worked steadily on these samples carrying out experiments no one had tried before. Noreen would call in weekly to give guidance and look over the immunology data. Noreen and I learned what it takes to do something completely different like this. Although I didn’t repeat that type of study, I am proud of it today.

|

| We shared a mass spec for years |

Meanwhile, Noreen spent her career learning the latest approaches to studying

old bones. As a Senior Scientist at the Smithsonian Institution (1988-2003) she

was one of the first studying ancient DNA, made antibodies to find diseases in

prehistoric humans, and coaxed small, million year old fragments of protein out

of ancient shells. After working with me on stable isotopes for many years, she

jumped out on her own, pioneering new methods in hydrogen and oxygen isotopes

in bones and teeth.

When Harvard University tapped her on the shoulder to join the Department of Anthropology in 2004, she readily took them up on their offer. It’s not every day one of your best Frolleagues gets an offer from Harvard. But, it was time. The Smithsonian was going through growing pains with respect to their analytical biology labs. Noreen spent two years getting the lab to function properly after a period of disarray. She was ready to be given a roomy office and a new lab.

Story #4 Wacky Isotopes: “Did you get the stones?” she asked, without even saying hello or how did the operation go. I was in Holy Cross Hospital recovering from gall bladder surgery earlier in the day. The surgery was a no-brainer compared to the disappointment I felt in failing to get the gallstones—my very own gallstones—to make the perfect isotope standard.

“They refused!” I had labeled a 50-milliliter plastic sample tube all ready to go, but recent laws prevented patients from obtaining their own body parts removed by surgery because they might be “infectious”. Come on—gallstones aren’t going to infect anyone.

The caller was none other than my friend and colleague Noreen Tuross. Noreen and I have proudly held up a bunch of samples we thought qualified as the weirdest or wackiest for years. In 1988, Noreen came to the same hospital armed with a Styrofoam bucket packed with dry ice to collect my placenta after I gave birth to my daughter. She was given it, without any fuss or bother. We were embarking on the nursing mother isotope study with me and my daughter as first subjects. It made sense to get the tissue interface. The doctor knew I was a scientist, so she wasn’t surprised by the request. In 1991, when my son was born, Noreen was there again. We have an n=2 (meaning two separate specimens) of my placentas.

For years we told the story over the dinner table. Dana and Evan were initially

appalled, then were kind of proud their placentas were in the Smithsonian, now

in a -80°C freezer at Harvard. It's a family joke. Noreen and I swore when we

were running out of ideas, nearing retirement, we’d analyze them.

Back then, it was much more difficult to analyze the isotope composition of a sample. The analyses were not automatic in any sense of the imagination. So when we analyzed a sample it had to be somewhat important.

Story #5 Turning herself into an

Isotopic Paleo-Indian: One of my favorite stories with Noreen is the time

she tried to turn herself into a “paleo Indian” [an American Indian before corn

was introduced in North America] with an isotope signature signifying a

complete lack of corn in her diet. In the United States, corn, either in

animal’s diets or from high-fructose corn syrup, influences most of our meat

supply, our dairy supply, and our sugary products. Therefore, when you analyze

human tissues, like fingernails for example, they are always labeled with a good

portion of carbon originating from corn.

Noreen’s diet included rice, lamb from New Zealand, vegetables, and baked goods without sugar. The lamb was expensive, so she didn’t eat much of that. She didn’t lose any weight, but after six months, she had more colds than normal.

“Do you think it's the weird diet you’re on?” I asked.

“Marilyn, I have a PhD in Medicine. I know what I’m doing,” she answered.

At 3 months, 4 months, and 6 months, she sampled her fingernails hoping to see the influence of corn diminishing, turning her isotope signature into a “paleo Indian”. At the old Geophysical Lab, the nitrogen isotope mass spectrometer was right next to my desk. The vacuum line for prepping samples was in the adjacent lab. Noreen worked the line; I ran the mass spec. The data came out printed on a dot-matrix printer, chugging line by line.

The 3-month sample was analyzed first. It takes roughly three months for fingernails to grow from cuticle to fingertip. We didn’t expect big changes and we were mainly looking for changes in carbon isotopes, not nitrogen. When the data came out, I looked. Noreen’s original nitrogen isotope signature was +10 parts per thousand (‰). It was slightly elevated: +11.5 parts per thousand.

The 4-month sample came next. Whoa—now it was +14 parts per thousand, quite a change. All of the biogeochemistry folks gathered around the mass spec, speculating on what this meant.

“Run it again,” Noreen suggested, which I did. The same value came up again.

|

| Mat Wooller, Paul Koch, Matt McCarthy, Noreen, Jake Wakdbauer |

The 6-month sample was next. By this time, we were laying bets on what the value would be. The analysis took about 15 minutes—and we watched as the printer spit out a value of +16 parts per thousand.

I ran it again to make sure. Chemistry and physics did not lie.

What does this mean? It had been hypothesized that when an animal was in negative nitrogen balance, they metabolized their own tissues to get enough protein to keep them alive. When this happened, the lighter isotope of nitrogen (nitrogen-14) was excreted, while the heavier isotope (nitrogen-15) remained. Noreen’s increased value going from +10 to +16 meant that she’d been surviving on her body’s reserves, something you want to avoid.

“Don’t tell my husband!” she said. We didn’t, until nearly 25 years later after I’d told the story a million times to other people. He merely shook his head, knowing his brilliant, but feisty, wife was capable of almost anything.

The diet ended that day. Noreen’s carbon isotope pattern never reached that of a paleo Indian. It takes a lot to turnover the tissues in a human body.

Story #6 ALS and Life: In November of 2014, I was in Kiel, Germany, attending an isotope conference for anthropologists. I was walking to the meeting from my hotel with Noreen Tuross and her postdoc Linda Reynard. I was dressed in a sharp black dress, purple woolen jacket, and low-heeled purple boots, when suddenly my ankle buckled. I landed hard on the ground. Noreen and Linda helped me up, and we went on our way. The walkway was made of cobblestones, and I blamed the boots and the cobblestones on my fall. Weirdly, I fell two more times before reaching the conference, then flanked arm in arm with Noreen and Linda. I walked home in stocking feet and gave away the purple boots. It was my first sign of ALS neurodegenerative disease.

In 2016 after the ALS diagnosis, Chris and I moved again, now to UC Riverside. I had to start all over again, building the lab and making personal connections. This time it wasn’t as easy as it was in 2013. There were a few disappointments.

“I thought we’d be further along than this,” Noreen said as we discussed how women fare in academic departments, particularly as we’ve aged. As the only senior woman scientist at a major research institution for about 35 years, I grew up and was used to the trials that women face during graduate school, postdoc training, job hunting, grant writing, and lab building. It was tough. I had to learn how disabled people were treated. I prevailed.

|

| Steve Shirey, Noreen, Larry Nittler, Conel Alexander, Marilyn Madness, 2016 |

I am fortunate to have made a lot of my career’s journey with Noreen. We continue to email about life’s challenges from across the COVID divide and I hope to see her again—no idea where or when. Knowing that you have friends or Frolleagues with the longevity and import of someone like Noreen Tuross makes you “never give up.”

Thoroughly enjoyed reading this. I have followed both you and Noreen ever since working with Larry Tieszen on isotopes in Bison bones and in Andean mummy tissues. I was thrilled to meet you both in person. Wishing you well. With great admiration.

ReplyDeleteI am curious...did you ever analyze your placentas?

ReplyDeleteNot yet. I think the time is near at hand, but with COVID-19 lab access is limited.

ReplyDelete